Select one reading from the course reading list and ‘re-present’ its main arguments and ideas using the

structure,

form, or

method

of another on the reading list.

To translate the structure of Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino (1972) onto another text, the pattern of the book must first be examined. The text is guided by a framework of fictitious conversations between Venetian merchant, Marco Polo, and the former emperor of the Yuan Dynasty in China, Kublai Khan. The conversational tone of the text creates a whimsical representation of the architectural principles of the 13th Century, bridging the gap between Eastern and Western design. Calvino (1972) creates a tension between the real and surreal in Invisible Cities through the imagination of the conversations between these two historical characters.

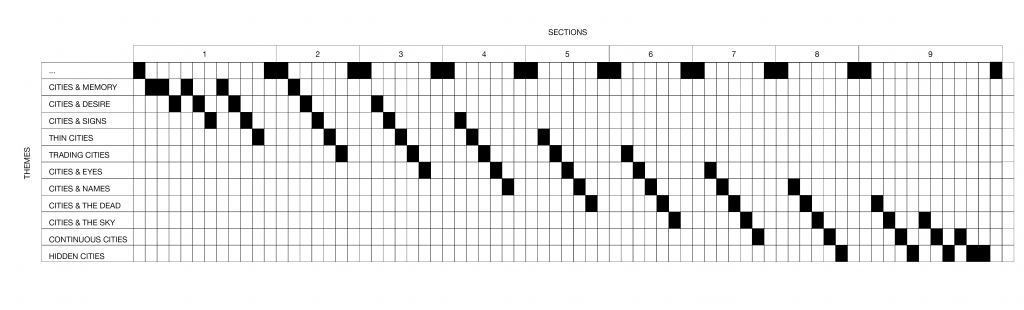

The 55 invisible cities are catalogued into eleven themes. Calvino (1972) adopts a non-linear structure, where these themes are woven into nine sections of the book. This non-linear pacing magnifies the overarching topics of the book, particularly memory. Similarly to memory, the structure of the book is cyclical, with themes being reviewed periodically. Representing the configuration of Invisible Cities as a diagram further illustrates the cyclical system in which the themes are introduced and, subsequently, re-introduced (Calvino, 1972).

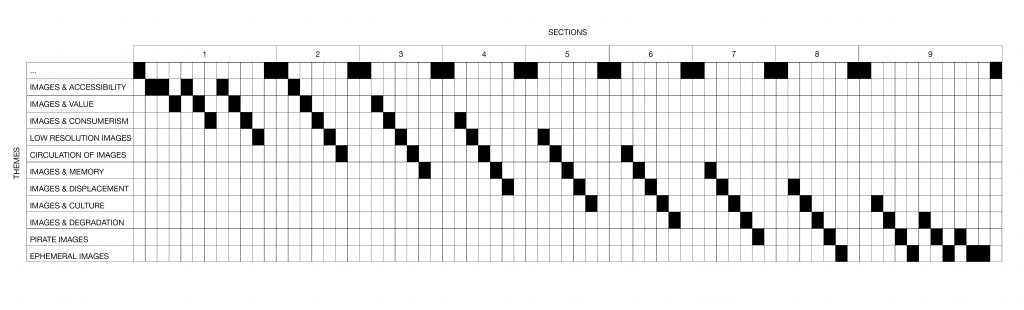

Applying the same structural logic onto Hito Steyerl’s In Defense of the Poor Image (2012) reveals different thematic strands, all in relation to the ‘Image’.

Overarching similarities, including memory and reality, can be drawn between Steyerl (2012) and Calvino’s (1972) texts. This informed the translation of Steyerl’s (2012) writing, which follows the non-linear, thematically catalogued structure of Invisible Cities, rather than a translation into dialogue (Calvino, 1972).

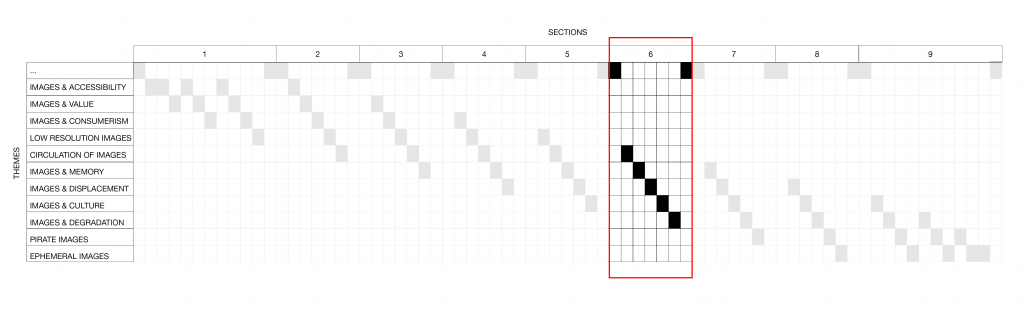

Due to the brief nature of this writing, only Section 6 will be re-presented, allowing for a more focused consideration.

Circulation of Images 5

Quality is transformed into accessibility. A poor image is created when it can be viewed by the masses, therefore quality of image must be surrendered in favour of widespread circulation.

Images & Memory 4

Memory attached to an image is implicit. Its memory is inherent as the quality reveals the history of its viewership.

Images & Displacement 3

The process of decontextualising enables co-ownership of an image. The semantics of a poor image will be altered, as it is uprooted from its original context.

Images & Culture 2

Commodification of images is reflective of the paradigm shift towards a culture of mass-consumption.

Images & Degradation 1

Incessant redistribution of images creates a visual uncertainty.

The circular nature of both readings is apparent; Calvino (1972) amplifies the non-linearity of memory through the structure of the text, whereas Steyerl (2012, p.43) repeatedly discusses the cyclicality of ‘distribution circuits’ of poor images. The translation of In Defense of the Poor Image, reinforces and further amplifies the notion of the poor image (Steyerl, 2012). The procedure of copying, reformatting, and redistributing defines a poor image. This same process has been undertaken during the structural translation of Steyerl’s writing (2012). The result: a ‘poor image’ of In Defense of the Poor Image (Steyerl, 2012). Through ‘re-presenting’ In Defence of the Poor Image (Steyerl, 2012), within the framework of Invisible Cities (Calvino, 1972), the text has become flattened, inevitably filtering out some of the themes and information discussed in the original, unaltered text.

Reference List:

Calvino, I. (1972) Invisible Cities. Translated from the Italian by W. Weaver. London: Vantage Books.

Steyerl, H. (2012) ‘In Defense of the Poor Image’ in The Wretched of the Screen. Berlin: Sternberg Press, pp. 31-45.

Leave a Reply